Break the Glass Ceiling! Why Women Deserve a Seat at the Presidency of the Ghana Bar Association

- IAWL

- Sep 3, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 11, 2022

By. J. Jarpa Dawuni, Ph.D.

In 1887, John Mensah Sarbah entered the historical record as the first Ghanaian lawyer when he was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn in London. It would take another 58 years before the first Ghanaian woman— Essi Matilda Forster (neé Christian), would be called to the Bar at Grays Inn in London, in 1945 and later to the Gold Coast Bar in 1947. Globally, the legal profession was emerged as a male-dominated profession, and women had to fight to be included— first, for the right to study law, then for the right to practice the profession. Despite the global feminization of the legal profession, women still struggle in the legal profession to be accorded the equality they deserve in the practice of law, and in leadership positions.

The establishment of the Faculty of Law at the University of Ghana in 1958, and the Ghana School of Law in 1959 by Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, opened the way for many Ghanaians to study law on Ghanaian soil. Unlike women’s experiences in the United States, the United Kingdom, and much of Europe in the early days of the profession, women in Ghana were not denied access to a legal education. Nonetheless, the colonial policies of limited basic education for the “natives”, and particularly for girls, and pervading socio-cultural practices, meant that the intake of women pursuing a law degree took time to grow. Since Essi Matilda Forsters’ historic achievement as the first woman lawyer in Ghana, Ghana has witnessed a gradual feminization of legal education, and consequently the legal profession, as more women acquire a law degree—with most of them graduating top of their class.

This brief historical journey leads us to the pathways women have taken after law school. A survey of the legal profession in Ghana shows that women can be found in all areas of legal practice—as in-house counsel, corporate executives, government agencies, law professors, judges, magistrates, associates, partners in law firms, and managing partners. Currently, women account for more than 30% of the members of the Ghana Bar Association. A recent study by the American Bar Association indicates that despite the increase in the number of women lawyers, women continue to face gender-based challenges leading to their slower upward mobility, and the high rates of attrition from the practice of law.

A report by the Institute for African Women in Law, Unveiling Subalternity? Women and the Legal Profession across Africa, highlighted some of the challenges women across the continent face, and these include handling the work-life balance due to the gendered division of labor in most homes, sexual harassment, workplace gender-based discrimination such as unequal pay, uneven promotion, and lack of access to networks. The challenges women face in Ghana mirror other global trends as documented by the International Bar Association’s Us Too? Bullying and Sexual Harassment in the Legal Profession.

Notwithstanding these challenges, women in Ghana have risen to top leadership positions. The symbolic representation of women in these positions indicates the existence of favorable opportunity structures for women’s leadership in law. Despite the constant wrestling with the ghosts of patriarchy upon which the legal profession was built, women in Ghana have forged a way forward in excelling at the profession both at home and abroad. Women lawyers in Ghana have demonstrated their leadership capabilities including holding the top judicial position as Chief Justice, and the table below provides a few of these gains:

Among some of the top-ranking law firms in Ghana, women are well represented as partners and managing partners:

Women and the Leadership Debacle

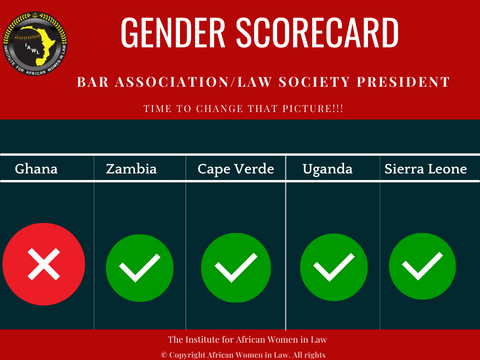

The data demonstrate unequivocally that women have made great strides within the legal profession notwithstanding the myriad of challenges they face. Why has the leadership of the Ghana Bar Association (GBA) remained a promise land yet to be reached by women? Harveys (1966) Law and Social Change in Ghana, traces the formation of the current GBA to its predecessor, the Gold Coast Bar Association in 1904, despite the formation of the Superior Courts of the Gold Coast Colony in 1887. Since the establishment of the GBA in Ghana in 1958, the leadership of the GBA has been held by men. Despite the demonstrated leadership of women in all the major areas of the legal and judicial practice in Ghana, why has the GBA presidency remained under the exclusive leadership of men? Is the GBA still operating under the notion that “there are no women at the Bar?”

Why Women Deserve a Seat at the GBA Presidency

Felicia Gbesemete, a veteran lawyer came close to holding the top leadership position within the GBA when she was elected Vice President of the GBA and served from 2004 to 2007. Since then, no woman has had the opportunity to lead the GBA at the national level. The absence of women in the top two leadership positions—President and Vice President is not because women have not contested for these positions. One of the two contenders in the current election cycle is Efua Ghartey, a lawyer with over 30 years of practice at the bar, and has served as the President of the Regional Chapter of the Greater Accra Bar Association for two terms.

Efua Ghartey is not new to this game. She contested for the position of President of the GBA in 2018 and came in second, losing by only 67 votes. Will this second time be the charm? The answer depends on how we adhere to the practical steps offered below. Various theoretical frameworks explain the challenges women face in accessing leadership positions. Additionally, phrases such as the “glass ceiling”, “treading water”, the “leaky pipeline” and the “old boys’ networks” have been used to explain the lack of women in leadership positions. In the ensuing discussion, I adopt a problem-solving, solution-oriented approach to highlighting why women deserve a seat at the GBA presidency.

Women in Ghana have shown from the Makola market to the executive boardroom of global corporations that women know how to lead.

Women in Ghana have shown that when favorable opportunity structures exist, women can lead the country successfully as they did as Chief Justices.

Women in Ghana have demonstrated that when granted the opportunity to lead as deans of law faculties, they lead with excellence and leave behind a legacy, including constructing a law faculty building fit for the University of Ghana School of Law.

Women in Ghana have shown that they can lead top law firms as managing partners and as a majority of partners in some of the leading law firms in the country.

Women in Ghana have shown that they can serve in international courts and tribunals as judges, contributing to global justice and human rights.

How do we create equal opportunities within the GBA Presidency?

Elections to the presidency of the GBA has become a highly politicized charade. Historically, the GBA president has been a key player in national politics, including serving on important boards and constitutional selection committees. The GBA President has also been a vocal proponent of the voices of members of the Bar vis-à-vis the government. These roles have meant that the prestige and power accorded to the GBA presidency has increased over time. It is time for the GBA to move from power politics to equality politics.

Practical Solutions from Power Politics to Equality Politics

Men[4] must be allies in the global movement for gender equality

Men must value the leadership capabilities of women— which are on display every day from the courtroom to the boardroom.

Men must re-socialize themselves to believe that the old age “gentlemen at the bar” is an archaic, outdated, and regressive colonial heritage that must be thrown out.

Men must be intentional in their choice to promote and support women in leadership

Women must support women. Women make up more than 30% of the Bar. If women support women, the critical mass can push and tilt the pendulum in favor of a compelling woman candidate.

Women voting for women is not gender politics. Women voting for women is the recognition that symbolic representation is the first step to substantive representation.

If women can lead the judiciary of Ghana as Chief Justice, lead the law faculties as Deans, and lead the nation as Minister of Justice and Attorney General, they can surely lead the GBA as President!

Ghana continues to be a trendsetter in the legacy of women in law across Africa. It is time to raise the stakes. It is time to demonstrate that women can lead in all areas of the law—including the presidency of the Ghana Bar Association.

It is time to change that picture!

[1] International Criminal Court (ICC)

[2] African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACtHPR)

[3] United Nations Administrative Tribunal (UNADT)

[4] I am conscious of non-essentialism and recognize that not all men feel, act, and think the same way. My usage of the phrase “men” does not mean a blanket application to all men, but only to those who fall in the categories of the prescribed needed change.